A woman with an Acquired Brain Injury says she waited more than six months for National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) funding.

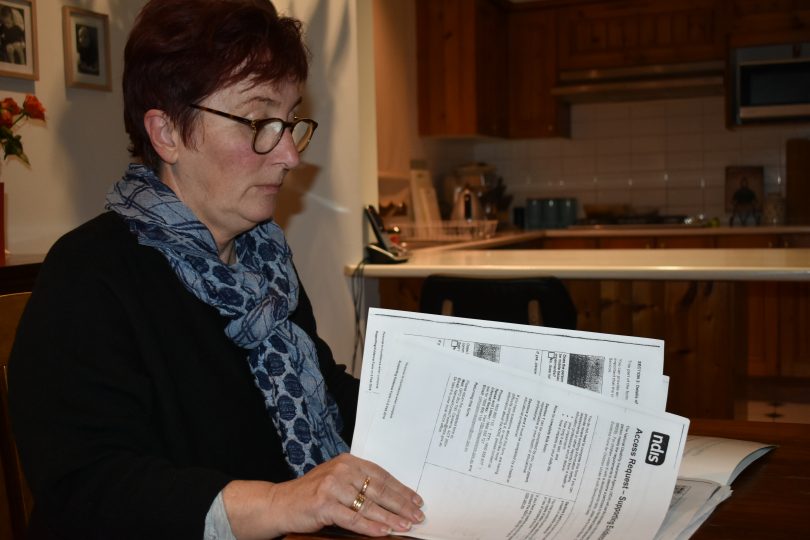

Beth Stewart lives with an Acquired Brain Injury as the result of a car accident several years ago.

Prior to the rollout of NDIS in her area, she received support under the old disability system.

When the scheme arrived in her area, her case manager helped her to apply and collect all the necessary paperwork.

This turned into “a long, hard process”, which she describes in the video below.

After months of waiting, Stewart finally got the results.

She had specified all communications should go to her case manager, but the letter was sent to Stewart instead.

Despite the time taken to get there, she was happy.

She received the funding she needed.

“It was great,” she says, pulling out the letter with a smile.

But she would still like to see waiting times reduced, and the application process simplified.

She’s also quick to point out the help she received from her case manager, who regularly ‘hassled’ the National Disability Insurance Agency (who oversee the NDIS) on Beth’s behalf.

“My case manager put me through it all, if I didn’t have him, I wouldn’t know what to do to even get the NDIS.”

A bus drives past a bus stop in outer Melbourne. Beth is unable to drive because of her brain injury, and receives funding from the NDIS to cover public transport costs.

Beth is not the only one who thinks it was important she had somebody on her side.

Dr Bruce Bonyhady was the inaugural Chair of the NDIA and is often referred to as ‘the father of the scheme’.

He says “the NDIS is working for most people and in many cases, it’s producing outstanding results, but there’s a clear group for whom it’s not working”.

Dr Bonyhady believes this group is made up of people who cannot advocate for themselves, and do not have someone to do so on their behalf.

He says this goes against the very idea of the NDIS. “It was designed to be fair.”

The scheme was meant to replace the old disability system whereby state and territories all had different schemes for different disabilities, which varied from region to region.

The NDIS has been slowly rolled out across Australia since July 1st 2016 on an “ambitious” schedule.

Dr Bonyhady says the old system’s “postcode lottery” has now been replaced by the luck of whether you, or someone on your behalf, can advocate for a plan.

One place where people can find an advocate, is at Melbourne East Disability Advocacy (MEDA).

MEDA Program Manager Jan Mattrow says the NDIS has been “life-changing” for some people, who found the process “quick and efficient”.

“Whereas others have felt dis-empowered and frustrated with their experiences” and faced “lengthy delays”.

Jenny Connor, a paediatric occupational therapist in Melbourne’s North East, has seen some of these delays in her work.

Last year she submitted a report for a family, explaining why their pre-schooler needed early intervention support from the NDIS.

The mother contacted Connor recently to say they had now received their plan.

That funding was supposed to provide supports for their child before they started school.

They’re already in term two.

Connor finds it “very frustrating,” that early intervention funding took this long to be approved.

“It’s a critical time. The youngsters are the ones you want to get to early, and they’re being held up.

“When people first get a diagnosis or have an issue with their children, they shouldn’t be faced with all this red tape.”

Connor has not just seen long waiting times in participant applications, but also in her own application to register her business for the NDIS.

“It’s been a frustratingly slow, slow process to get approved as a service provider…I haven’t heard anything since the end of February.”

(A few hours after the interview concludes, my phone pings. It’s a text from Connor, who received an email saying she’s now approved for early childhood services).

She describes answering repetitive questions and uploading zip-locked files with pages and pages of evidence, only to be told she needs to provide more.

“The whole process is laborious.”

Connor’s frustration with the NDIS’ bureaucracy is shared by many.

MEDA’S Jan Mattrow says navigating the NDIS “requires a degree of skill, confidence, resilience and often articulation”.

Articulation came up during Stewart’s application process.

As a result of her ABI, Stewart has issues with her balance and needs a bath rail for her safety.

When preparing Stewart for her meeting, a support worker insisted Stewart was particular with her words.

“You have to ask for bathroom modifications instead of a bath rail.”

(For those wondering, Beth followed the advice and did receive funding towards modifications).

Another frequent complaint is the perceived inconsistency of funding decisions.

Connor says she sees families in similar situations with “very different packages”.

For Stewart, the system doesn’t seem fair.

“It just depends on the assessor on the day, or how well your doctor has written your letter”.

Despite the issues mentioned, everyone interviewed agrees on the benefits of the NDIS.

Stewart used to work for Vic Rehab, which dealt with a lot of TAC claims.

She saw first-hand the discrepancies in funding under the old system, where the name and/or cause of ones’ condition essentially determined the funding received.

“I looked after kids who’d had strokes or were born with cerebral palsy and…their parents had to pay for their wheelchairs. But the kids who had car accidents got a wheelchair [through the TAC].

“So the idea [of the NDIS] is good, but I don’t think they have explained it well or been consistent.”

Connor also agrees there are positives to the scheme.

She speaks of families who are “very grateful” to receive funding that wasn’t there before.

“It’s just all the red tape and inconsistencies, but I do feel it will slowly improve.”

So how will the NDIS improve? Dr Bonyhady has some ideas.

To take out the red tape, he says there needs to be more support for those who are not eligible for the scheme.

“The NDIS is like an oasis in the desert. If you’re not eligible for the NDIS there is virtually no supports available to you. At the edge of the scheme, there is a cliff, where the last person in can get thousands of dollars and the first person to miss out gets nothing.”

Increasing funding for this ‘second tier’ will ease the pressure people feel to try and qualify for the NDIS and mean it can “be much less bureaucratic”.

It will also ensure people outside the NDIS get more support, without which they may end up needing to enter the scheme later at a higher cost.

To tackle waiting times, Dr Bonyhady says the NDIA must lose the staffing cap which prevents it from hiring more people to deal with the backlog of work and upgrade its IT system.

The IT system was “never fit-for-purpose, never worked as intended,” and, along with the staff cap, “had a profound impact on the rollout”.

He’d also like to see researchers granted access to de-identified NDIS data.

Dr Bonyhady says this data would give them “the potential to make NDIS the best disability service in the world”.

When asked why it’s so important Australia gets the implementation of the NDIS right, his answer is simple.

“I just think it’s about fairness. If we want a fair Australia, then the NDIS has to work as intended”.

The NDIA did not respond to requests for comment.

Jan Mattrow is the Program Manager at Melbourne East Disability Advocacy. However, she would like it noted she is not an expert in the NDIS.