The Cannings Reserve in the inner-western suburb of Maribyrnong is nothing short of idyllic. On this late yet sunny autumn afternoon, the sun reflects off the river which is flowing quickly after a significant bout of rain. Mums are out walking their babies in prams, while uniformed children laugh as they make their way home from school on the riverside tracks. Yet it’s impossible to ignore the eyesore that is the rusted tin building just over the top of the hill – one of the many buildings belonging to the now defunct Maribyrnong Defence Site.

The Maribyrnong Defence Site

A defence site building visible from the adjacent Cannings Reserve. Pic: Bridget Clarke.

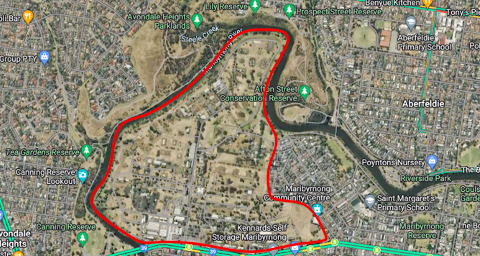

Driving west from Melbourne’s CBD along Maribyrnong Road provides a sense of just how big the site is. For two kilometres, the driver side view is dominated by empty and rusted factory buildings tucked away behind chainmail fencing. The only accessible entryway is via Cordite Avenue – an echo of its history as an explosives manufacturing site. A Google Maps search shows the site has three kilometres of river frontage.

Purchased by the Commonwealth in 1908, the 128-hectare site was used for weapons building and testing until its closure in 1993. In 2006, the site was effectively abandoned by the Department of Defence, prompting talk of redeveloping the land for housing. But there was just one small issue that would keep its development in stalemate for decades to come.

Three kilometres of the 128-hectare site backs onto the Maribyrnong River. Pic: Google Maps.

“Dangerously Contaminated”

Decades of audits into the Maribyrnong site uncovered a pattern of environmental and waste mismanagement. As the largest urban infill centre in Melbourne, its dire state indicated the urgency of its remediation. A report released in 1994 by the now-defunct Australian Defence Industries body uncovered a drainage gully contaminated with elevated levels of copper, lead and zinc. In 2010, then Defence Minister Greg Combet confirmed the site was contaminated with up to 130 harmful chemicals. Asbestos has also been found.

Defence officials told a parliamentary inquiry in 2015 that a $50 million remediation had already been completed, and there were no immediate health risks to neighbouring residents. Yet the details of what was done are still unclear. Questions over the extent of the contamination, and the amount of money and time necessary to deal with it, remain.

20 years of handovers

The question of who is responsible for the clean-up of the Maribyrnong Site has halted its development for 20 years. Sales of former defence sites to private investors is common, the covering of remediation costs by the Defence Department itself is not. According to the department website, the covering of remediation costs – an estimated $200 million for Maribyrnong – is dependent on the extent of contamination and proposed use of the site. But that hasn’t stopped both state and federal governments proclaiming their commitments to redevelop the land for housing.

From 2003, Defence worked alongside the Victorian state government to sell the site. Seven years later, the government proposed the land could host 3000 homes – a vision that was never fulfilled.

In 2017, then treasurer Scott Morrison proclaimed the “landbank was open”, doubling the previously suggested figure to 6000 and putting the site up for sale on the open market. Despite interest from several investors, no sales were finalised.

Speaking with The Age last September, Assistant Defence Minister Matt Thistlewaite said it was “still possible” that the Commonwealth would pay for its decontamination. No other details were given.

And since then, nothing.

“It does seem absurd”

While Victorian Liberals Leader John Pesutto concedes the constant shifting of responsibility is “deeply frustrating”, he maintains that the Commonwealth should be responsible for handling the remediation of the Maribyrnong Site, not state governments. Like other government figures before him, Pesutto agreed the land should be used for “housing or community purposes”, adding if he was Premier, he’d “be pushing very hard to expedite that process”.

Talk of developing the land for housing has been questioned by housing advocates. For YIMBY Melbourne’s lead organiser Jonathan O’Brien, development of sites like Maribyrnong are not the silver bullet solutions to the housing crisis they have often been presented as, but rather, a distraction from “where the big gains are to be made”. To O’Brien, the Maribyrnong Defence site is a “blank slate site” that is “expensive, and quite difficult to service”.

And so, the debate over the handling of the site continues. Even through several state and federal government changes, fizzled proposals, countless environmental impact reports and a worsening housing crisis, the Maribyrnong Defence Site – dangerously contaminated and fenced off from the public – still stands, with no current plans for its future.