If you’re finding this season’s puffer jacket just isn’t warm enough, the key to better insulation testing is at hand.

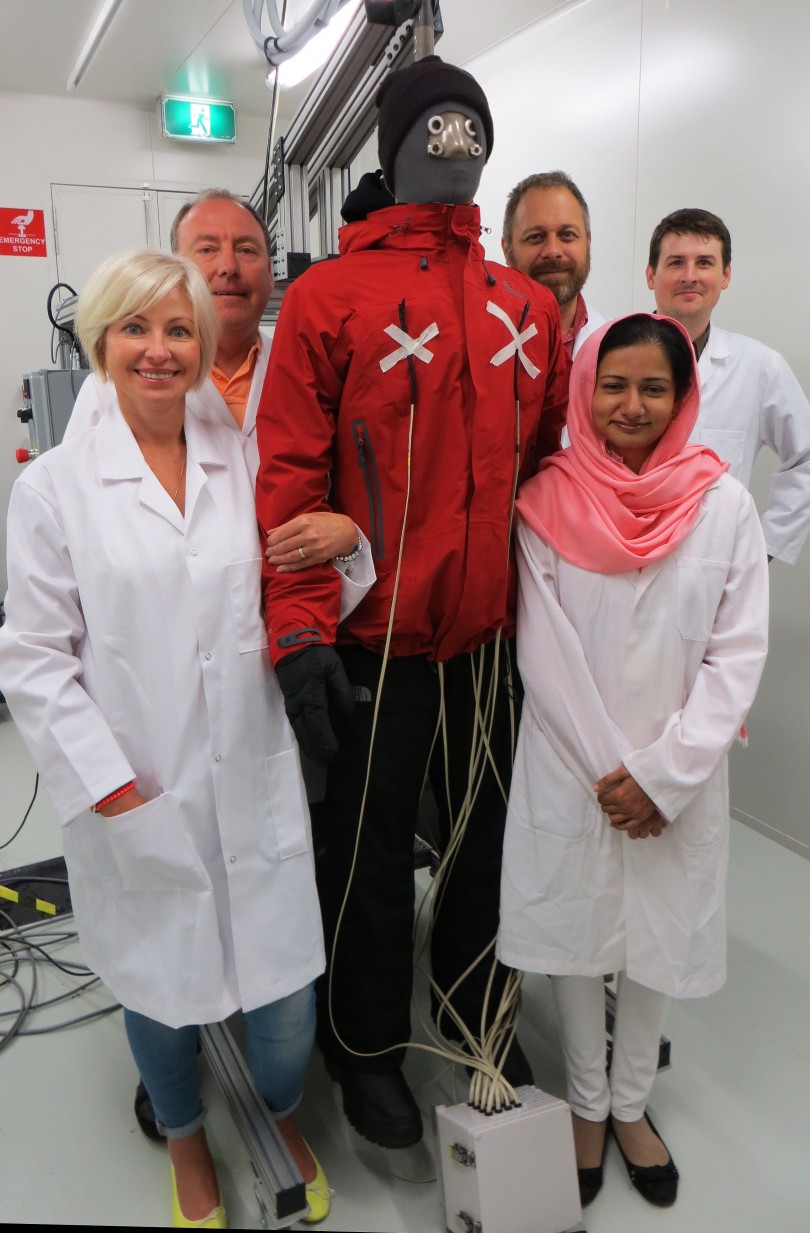

Researchers at RMIT University have created a clothes-testing $250,000 manikin called Newton – one who is responsive to temperature, meaning that it can freeze and sweat at will.

Performance and Sport Apparel Research Leader at RMIT’s School of Fashion and Textiles, Associate Professor Olga Troynikov, told City Journal this presents a new way to fast-track “meaningful data”.

“Fabric and garment trials using human subjects require extensive set-ups, and the variation is very high. Newton is designed to replace the human in a way because he’s objective,” she said.

How It Works

Newton is the average size of a human male – a size medium in Australia – and he’s made from a carbon fibre shell, making him very light. He works through a series of joints and sweat pores designed to mimic human bodily functions over 20 segments from head to toe.

Data from Newton is collected internally and externally. Software controls each of his segments, allowing researchers to set up his skin temperature and sweat rates, and to measure environmental conditions such as humidity and air movement using a series of sensors.

On the inside, he can measure the energy required to keep his skin temperature steady – akin to seeing how the body cools us down when we run.

But the same he can also be a she, as Newton has the option to be tested with breasts, which is crucial to understanding the thermal performance of female garments.

“Currently, a lot of female firefighters have to wear men’s jackets. Obviously, breasts make these perform in different ways as they add more angles and airspaces during wear,” Professor Troynikov said.

But seeing Newton sweat isn’t simply a matter of having liquid squirt out of a bunch of holes. Instead, he’s covered in a material akin to human skin, meaning that sweat spreads over his surface much like the human body.

What Will This Mean?

Newton is a boon for RMIT’s Fashion and Textile researchers, who have usually used unpredictable human bodies to test new fabrics and garments against climatic constraints.

While Professor Troynikov acknowledges that human trials “are ideal”, the costs, time and variations involved make Newton a convenient substitute.

Photography: Jazmine Thom

Hair and make-up: Ally Jenkins

Model: Nick Sampson

The same concerns are shared by designers.

Philip Luke Pedersen, who owns and runs menswear label Luke Arenholdt, says having access to something like Newton would make life significantly easier.

“Garments always look nice on a manikin for two minutes, but if you have a Newton in the studio, you could judge temperature and its suitability to different elements, which would dramatically reduce costs,” Pedersen said.

It’s no secret that the initial costs setting up your first ready-to-wear label are quite exorbitant. Most young designers are fresh out of a degree where university no longer provides a studio, fabrics, and equipment.

So when you couple that with the time and money you’d have to spend testing a garment over time with live models, the costs can easily blow out. But, having a more accessible Newton could avoid this, and allow designers to innovate in future collections.

“With how we use and treat our bodies now, we need to consistently progress with fabrics,” he says.

So the next time a polar vortex catches you out, keep in mind that the heir to the puffer jacket might not be too far away.