Over the last few years journalists and media institutions have been working to counter the spread of false information online – and media-literacy games are one possible antidote.

Communication technologies are changing and diffusing in society at a rate never seen before. Think of the online messaging service WhatsApp, which after its 2009 release gained more users during its first six years of existence than Christianity did in its first nineteen centuries.

But the rapidly increasing dissemination of media has been accompanied by a rise in disinformation and misinformation being shared and believed. It’s become a global problem reinforced by the fact that many people now receive most of their news from social media.

A range of media-literacy games have been created in response. Some get you to distinguish fact from fiction, while others ask you to play as an unscrupulous media magnate or fake website traffic generator.

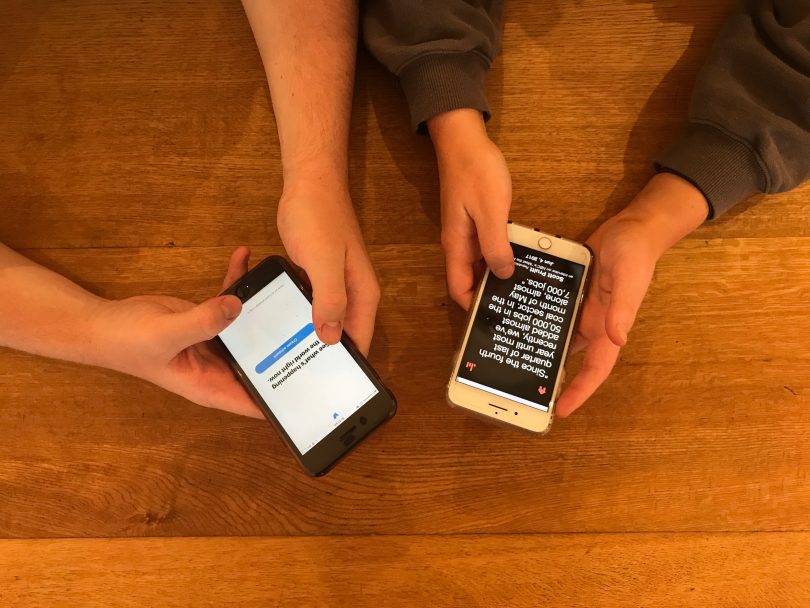

Filmmaker and game developer Chris Jarvis developed the digital game PolitiTruth in 2017 in partnership with the Pulitzer Prize winning fact checking organisation Politifact. In the game you swipe quotes to the left or right based on whether or not you think they’re true. And whether or not you’re correct, the app provides a link to the Politifact article which explains the claim.

“If I had to distil it into one phrase,” Jarvis says, “I’d probably say that it’s like Tinder for ‘fake news’”.

The words “fake news” have become ubiquitous. But in a 2017 piece for Medium, Research Director at First Draft News Dr. Claire Wardle says that the term isn’t actually all that accurate – apart from being an easy to use umbrella term – and points out the distinction between misinformation, which is the inadvertent sharing of false information, and disinformation, which is the deliberate creation and sharing of information known to be false.

Wardle says that our brains are increasingly reliant on simple psychological shortcuts because they are overwhelmed by a constant stream of information. This means that, the more times we read something, the more likely we are to believe it. And false information plays on our emotions.

“When humans are angry and fearful, their critical thinking skills diminish,” she wrote.

Games have the power to transform routine tasks, to make the mundane engaging. Games like PolitiTruth challenge our preconceptions of our own political awareness and media literacy – and they encourage us to think twice about what we read online.