“Broken Hill has come to symbolise the challenges and remoteness of living in the Australian outback.” (Broken Hill’s Heritage Listing)

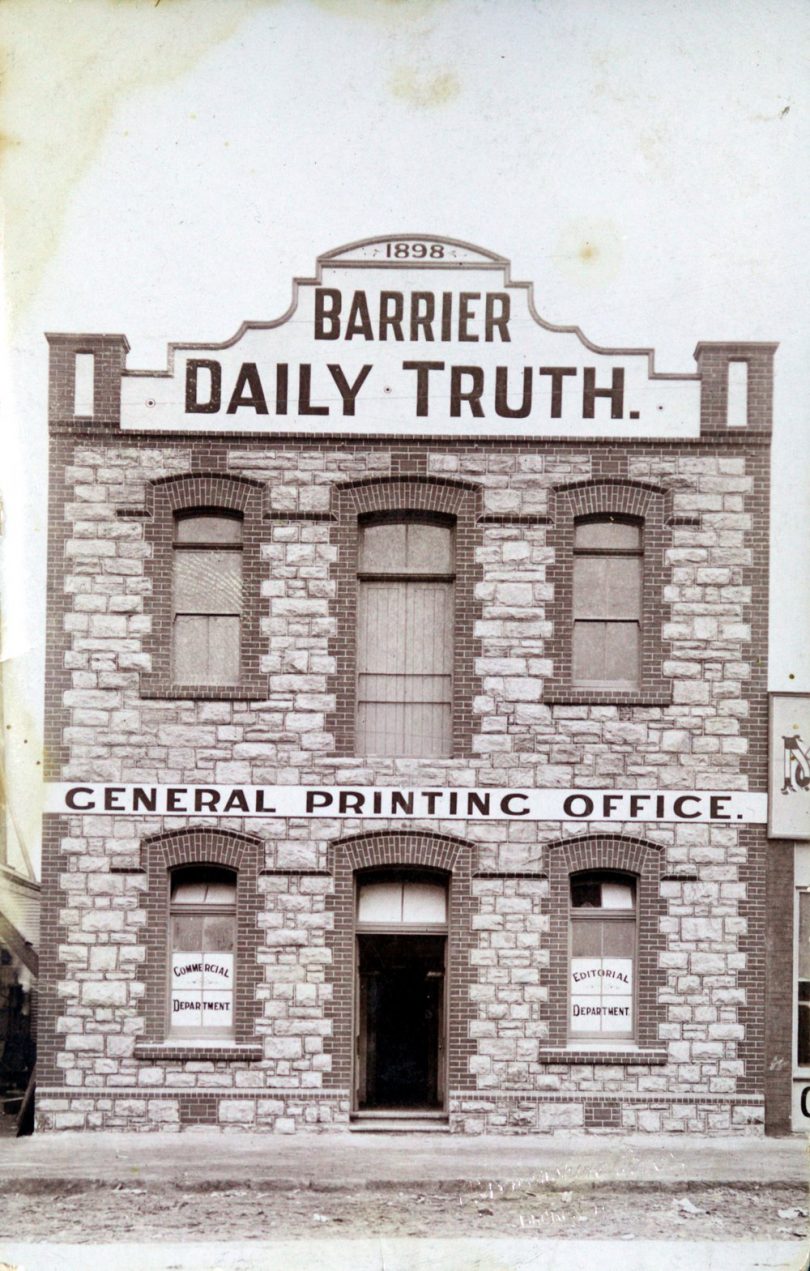

The Barrier Daily Truth (BDT) has been a staple of the Broken Hill community for 111 years.

But when advertising crashed as the global pandemic escalated, like so many other small Australian news outlets, the city’s only paper was forced to stop press.

The far-west NSW city is by no means a sleepy backwater.

It’s home to one of the largest lead mines in Australia, and one of the largest ore bodies in the world.

Broken Hill Proprietary (BHP) began mining in 1885 and the city has maintained continuous mining operations ever since.

The mullock heap looms tall over the main streets, which were named after compounds of lead – Iodide, Oxide, Chloride, Sulphide and Bromide Streets run parallel through the city centre.

An aerial view of Broken Hill. Image: Google Earth and Maxar Technologies

A black-and-white photo of the Barrier Truth Office opening in 1905 was on the front page of the BDT on Thursday, March 26, 2020.

It accompanied an article that explained why Saturday’s paper would be the last “until further notice”.

Readers were advised to monitor ABC Radio Broken Hill to stay informed.

Miraculously, a weekly edition of the paper was established in under a fortnight.

The Guardian reported how Robert Williamson, a mining executive based in Adelaide, born and raised in Broken Hill, worked to secure enough advertising to keep the paper going for a few months.

Erica Visser, a former BDT journalist living in Adelaide, said there was a sense of hometown pride among Silver City ex-pats.

“A lot of people originally from Broken Hill still feel strong ties to the city.”

Due to its geographical isolation, Visser said it would be a “devastating shame” if the city were to lose its paper altogether.

“If you buy the Sydney Morning Herald it’s not covering anything that’s going on in Broken Hill.”

Visser returned to Broken Hill with a journalism degree from the University of South Australia to begin her career at BDT in 2011.

She enjoyed the freedom to report on what interested her and said she was “pretty cutthroat” when reporting on local politics.

Water politics was a huge issue during her time at the paper.

Water is a particularly precious commodity in Broken Hill, a city of 18,000 people living in a region characterised by a persistently dry desert climate.

Some of her favourite stories were those she wrote about the nearby Menindee Lakes and Darling River drying up.

“An advocacy group formed representing Broken Hill, with a lot of disdain towards irrigators and cotton farmers upstream,” Visser said.

There was a commission and it was found the water was illegally let go upstream.

“It made national headlines and it’s popped up quite a bit. It was big on Twitter for a while.”

Lake Menindee was empty at times due to a lack of water flowing from the Darling River. Image: Pexel

A union-owned paper, BDT has a long history of advocating for the working class. The mines became a historical site for unionism in the early 20th century when workers were on strike for over 600 days, finally securing better underground conditions and a 35-hour week.

Murphy said he felt a responsibility to honour that history.

A few years back we re-printed the first edition of the daily newspaper. It drove home for me why the newspaper was formed in the first place. At the time, Broken Hill was pretty rough and ready, the industrial scene wasn’t good for the workers … And that was the reason the BDT was formed, to support the struggling workers and give them a voice. That’s something I need to honour.

Some readers have subscribed to the newspaper for more than half a century.

Murphy said the paper supports those older readers in different ways.

“The BDT is very important in terms of keeping people-centred, having something familiar that they can connect with like getting the paper in the morning,” Murphy said.

“Our role’s not only about holding people to account, keeping people informed and human interest stories … a lot of the older residents rely on it so they know what’s on TV.”

Visser said the BDT was part of a Broken Hill “media bubble”, which included ABC radio, another commercial station, community radio and a 30-minute TV news bulletin shared with Spencer Gulf in South Australia, 400kms away.

Connectivity issues were still an issue in outback Australia.

In the last national Census, 27 per cent of households in Broken Hill said they did not access the internet from home, double the national average of 14 per cent.

BDT journalist Craig Brealey reported the neighbouring Central Darling Shire struggled with patchy and weak mobile phone, internet and radio coverage.

ABC Broken Hill broadcasts were so faint in some parts of the shire that “travellers and everyone living in the shire were being denied local news and other important information,” the report said.

For those with internet access, Facebook provided a supplementary source of information.

One community group on Facebook, BrokenHillAustralia, began sharing local news and updates from across social media to fill gaps in local news coverage.

Levi, a group administrator, said the “strictly non-profit” page was run by a “loose collective” of locals who were concerned about the welfare of the Broken Hill community.

The group, whose members were mostly from mining, health and small business, preferred to remain anonymous and sought no recognition for their work.

“We have become, in a way, a de facto news source … we tend to cover what the ABC doesn’t and we keep a close eye on the happenings of the local council, it is the feeling we get they are not very popular,” Levi said.

“It is sad the BDT has scaled back its operations and we feel this has impacted the older generations.”

Levi said he thought some changes to the newspaper were positive.

“They have embraced new formats in the weekly issue we hope they continue with.”

Murphy agreed that although editorial decisions became a lot tougher with a weekly, it made for a better product.

“Some of the better papers have been put out in the last few weeks, in terms of local content and a sharper focus on what’s important and what’s of interest to the public.”

The front page of the Barrier Daily Truth on Saturday 28 March 2020. Image: Barrier Daily Truth.

In March, Murphy filled what he believed would be the last edition of the newspaper indefinitely with stories from the archive about local people, mysteries and legends.

He favoured stories about the people of Broken Hill, “quiet achievers” who spent their lives contributing to the community without seeking recognition.

“They’re the stories I really value. They’re difficult to get but so easy to write.”

In one story an abandoned public pool spontaneously re-filled itself with crystal clear water, and in another, a paralysed man learned to walk again.

There was a tribute to cameleers and profiles of more than one local sporting hero.

Another of Murphy’s favourite articles from the archive recounted Rupert Murdoch’s failed attempt to drive the BDT out of business by paying them to close down in the 1960s.

At the time Murdoch owned the Barrier Miner, the only other paper in Broken Hill.

University of Melbourne Professor Sally Young said that in the past the Barrier Miner was known locally as the “bosses’ paper”.

By studying archival letters Professor Young discovered the Broken Hill Associated Smelters purchased the Barrier Miner in 1918 to use as “a tool for combating union influence”.

The general manager of Broken Hill South Mine argued the BDT incited “class warfare” and industrial unrest and asked for “some means of keeping it within bounds”.

And yet, the Barrier Daily Truth, like so many people in Broken Hill history, quietly continued to defy the odds.

The offices of the Barrier Daily Truth and Silver City Printers. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Featured Image: A photograph of the Barrier Daily Truth office. Courtesy of the University of Wollongong Archive.