Media organisations have failed to protect female journalists and sources from online abuse.

Gender Equity Victoria reported that “a significant proportion of women journalists had experienced online harassment, trolling and stalking during the course of their work” in the report Don’t Read the Comments: Enhancing Online Safety for Women Working in the Media.

“There is no quick-fix for addressing gender-based online abuse of women journalists or promoting active bystander intervention, but that there is an increasing recognition that media organisations must take responsibility for the safety and security of their employees and commissioned freelancers,” the report noted.

Another report, from Plan International, said articles about female athletes received three times more negative comments than those about males, and 14 per cent of the comments directed at female athletes were sexually explicit.

Discussion of gendered abuse online was kick-started in March 2019, when a photo of Tayla Harris playing in the AFLW made global headlines because of the abusive, sexualised and derogatory comments made in newspapers and on social media.

The photo was removed less than 24 hours after being published on the 7AFL Facebook page.

The Irish Times reported “Furore over Tayla Harris photo shows how vicious social media can be”, but said deleting the photo was not the answer.

“Deleting the photograph, and Harris, from a digital discourse, does not silence the haters and the trolls. It silences her. It silences the athletes. It silences everyone whose identity was vilified in those comments,” Irish Times journalist Kasey Symons wrote.

Tayla Harris on the field for Carlton Football Club. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Journalist Kate O’Halloran, a former sportswriter and commissioning editor for The Guardian, agreed deleting the photograph did not address the issue.

“I think part of the problem is that, at the moment, and this happened with AFLW and the Herald Sun, they just decided to shut all the comments on any AFLW articles…I think it’s kind of lazy, I think there are strategies that can be put in place to moderate comments.

“It’s an implicit expectation of your role that anything you do write, you then share on social media and in some way engage with the audience response to that and the comments that come with that. Because even if comments are turned off, from an organisational perspective, they are not necessarily on your social media, so you are exposed to that more immediate social response,” she said.

Gender Equity Victoria recommended “a whole-of organisation approach to address systemic and structural sexism in the workplace” and “treating gender-based abuse against women journalists on social media and websites as an issue of workplace health and safety” to better protect women in media.

Gender Equality Victoria will soon be trialling a new tool at RMIT: a short quiz readers must pass before they can comment on certain articles.

NRKbeta, the online branch of the Netherlands public broadcaster, has also used the tool.

Kate O’Halloran said the quiz could be useful, but media organisations need to dedicate more resources to moderating comments.

“When I was at The Guardian, their approach to anything controversial was just to shut (down) the comments. And for me, that was always really disappointing, because it is about people power.

“How many resources do they have? How many people are moderating that day? What are they dedicating their time to? Do they have someone to spend four hours moderating the thread on my work, or do they need them for something else? I think it has become a sort of default to say, ‘Let’s close the comments’, but then you don’t have a discussion,” she said.

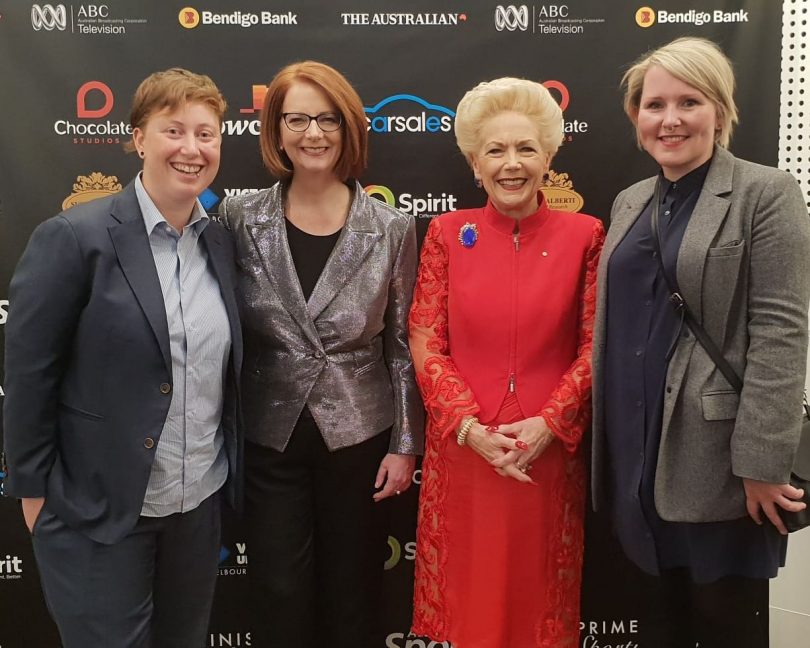

Featured Image: Kate O’Halloran, left, attending the Prime Ministers’ Sporting Oration. The event supports grassroots sport and the impact it can have on the health and unity of all Australians. Photo supplied by KATE O’HALLORAN

Great to read dialogue surrounding this shameful practice, and agree that removing comments fails to address the root causes. We need more exposure and discussion of the systemic ugliness of gendered abuse online , good work.

“treating gender-based abuse against women journalists on social media and websites as an issue of workplace health and safety” – while this seems like a worthwhile initiative, and organisations need to take responsibility when their employees are exposed to abuse, it does sadden me that the response to the abuse is about the victims’ workplaces. I feel like this sort of abuse is not restricted to women journalists and would love to see some kind of broader response… 🤷♀️