We have lived with borders as soon as we could drag a stick through the sand or build a wall of stones. Borders have defined country, people, life, and death. Covid-19 has ignited awareness of these once soft for some but now steel tight for most, delineations of land.

Waves made by car tyres, doughnuts on the sand. This was not a place to go after dark without good friends. Under the endless sky, wide streets, and long twilights. It was the smallness of the town, felt keenly by teens, that moved us both away. A generation apart, you the braver travelled much further than I.

I have looked many times at this photo of Oreti beach, flat space in abundance. Perhaps you have seen this beach. It was a location for the 2005 film The World’s Fastest Indian, which tells the story of Southland’s motorcycling hero, land speed world record holder, Burt Munro. Less known is that at the other end of the beach in 1910, Herbert Pither, unwitnessed, completed a one-minute controlled powered flight. If true, it would be the first in New Zealand.

Sand, sea, and weather mark Oreti beach, the rounded end of Aotearoa, New Zealand. Here, the destination of our childhood holler “let’s go to the beach,” memories of you happy, restful. Propped against the driver’s door of our green 1979 Ford Cortina, soaking up the burning summer sun, when it finally arrived. Here would be the place that I wanted to say goodbye.

Oreti beach is the central bay of three that face Foveaux Strait. A 130 kilometre stretch of turbulent water separating the South Island from New Zealand’s third-largest island, Stewart Island/Rakiura (glowing skies). The Wawa-waiau or Hua mate, death wind as it is known by local Ngāi Tahu, swirls this bite of passage. In 1823, French naval officer Jules de Blosseville encountered these west north-west winds. “Whirlpools are frequently to be met with, and the position is one of great peril.” Today’s catamaran journey, Bluff to Oban, a little over an hour, is mild in comparison. Any talk of peril is a nod to the stock levels of the region’s famous delicacy, the Bluff oyster.

You hated that cold water, a bitter 10 to a balmy 16 degrees in the height of summer. You never went in swimming but let us go free. We propelled ourselves into those waves hitting them like cutting through a finishing ribbon. “She’s gone.” With these two words, the long journey was over. My mother old and ill, complex, and loved, died in June 2020. Not of Covid-19 but cancer, 2142 kilometres away in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Covid-19 has filtered our thinking, our actions, daily totals headline our news. The death toll remote in its largeness and piercing in proximity has created a global sorrow. It has taken away our ability to enact collective grief. Locked some in, and others out. In the saddest of circumstances, many are confronting the reality of borders for the first time.

The day before my mother died, she had taken a turn for the worst. I watched Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand Prime Minister, announced in measured and clipped tones, the removal of compassionate leave exemptions from the 14-day quarantine regulations. “This is not a popular decision, but it is the right decision,” she announced directly to the camera. I watched sitting in Melbourne, my home for longer than intended. Acutely aware of my grounded location, I willed my mum to live, a little longer.

As people age or are terminally ill, you ponder the lasts. The last Christmas. The last birthday. The last visit. These lasts are replaced with living in absence. I remember being told at my father’s funeral over 20 years ago, to steady yourself for the year of firsts. The transition of living with, to without, is hard and personal. For us, we wake. Generations gather, the deceased laid out in a family home. In those raw, peeling grief days, family-friends-food-stories-tears-laughter hold you. Life and death mingle a while, closer than we are used to, in this century, in this place.

Sitting in a draughty lounge room, the grey Melbourne June light echoing my inner dread, I watched mum’s funeral online. My family whānau, did us, did her proud. Stark laptop light highlighted the place I should be. I mourned my mother and the loss of our shared enactment of grief. Distance framed my sorrow. We live with distance as conquerable. This year 2020 has made us acutely aware of the distance. Our friend. Our foe.

Your slow boat travelled far from Makarewa, your small rural home. Older in a big family, earners and independence were essential. Your jumbled photo collection, black & white 2 by 3, record your working history. As children, we gazed on meter box London where you lived “on the smell of an oily rag.” “Killed by kindness” in Monto QLD outback. Dar es Salaam liquid honey to our ears. The isle of cloves, sweet-spicy, Zanzibar’s aroma ignited our imagination. We held the wonder of other worlds in our growing hands.

Souvenir booklet. Purchased 1950s at Zanzibar Airport Gift Shop. (Annaliese Forde)

I return now, my hands lined, to the small collection of photographs I carried away with me, on that last trip home. I see your youth, your verve, always careful how you looked in each frame. A favourite of mine, you posing, laughter promising, I see it shaking in your shoulders, you hold the off-centre pose for the one snap opportunity. It shows freedom in your body, lost in later years to hard work and responsibilities. The place, there is no clue, no words on the back, you said you would get around to it one day.

How close you brushed to illness and disease, life and death all of your working days. Dispensing hygiene and comfort, the back-crushing work of a Nurse Aide, overseen by to the book Matrons. Reading archives of Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, a nursing recruit recalls the Sister instructing them to treasure their uniforms. For the trust it inspired in their patients, “they will tell you things they never would if you were in plain mufti.” Mum, I wonder how many secrets and fears you held.

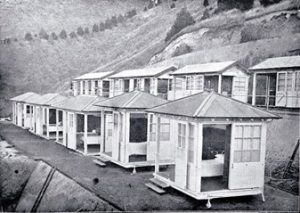

The tuberculosis hospital, Cashmere Sanatorium, Christchurch, was one of many hospitals my mother worked. It housed four institutions in the one. Three sanatoriums Upper, Middle, Lower, lined the hills. The acutely ill moved to lower san closer to their final resting ground. A children’s home, the fourth tier topped the hill. Treatments were rudimentary and gruelling. Hospital stays lengthy.

Women’s shelters at the Cashmere Sanatorium 1913. Open to the elements. (Christchurch City Libraries: CCL Photo CD 9 IMG0021)

Exposure to the elements, sun and fresh air deemed the best hope. “… those easterly winds and that misty rain, everything… damp“. Accounts of middle san housed in individual huts open on three sides exposing them to rain, wind and winter. A patient recalls “aching legs from the cold …waiting for the night nurse to come around at two [am]. She would refill our hot water bottles, and you’d cuddle it like a piece of gold.”

Never travel with empty hands, was the phrase that echoed around our house. Pick-up, put away, pull out weeds, flick the duster, tidy, washing in-out-folded-away. Journey with productive purpose. Mum your hands never still, tap-tap-looping an evening song, knitting love into neat rows.

Grief suspends gravity. The body scooped out gutted ought to be light. But it continues with a weight that should tremor underfoot to passers-by, my loved one has died. Instead, the life of the ordinary endures. The hollow self carries on. My mother’s death like so many things this year is knotted with COVID-19. This pandemic has interrupted our enactment of collective grief. It closed barriers around people and relationships, time and place that I yearn to farewell.

It has unhoused the indignities, that we accept for other people, in their living and dying. Perhaps for the first time, many of us, as Deborah Cheetham said when speaking of the permits and curfews imposed on her Aboriginal grandparents, are “experiencing a tiny sliver of … deprivation.” As we live with and leave this pandemic to history, we have many presents and pressing truths to face.

Once we have reclaimed, as the song goes the Beauty of Everyday Things, as a memorial to our collective losses and imposes sorrows, let us journey with productive purpose and act in common for good. In time, I will return to that 26 kilometres expanse of perfectly smooth Oreti sand. Feel, even on the warmest of days that cutting wind travel my body, sculpturing the deep south ways back in.

I won’t rip up the sand with speed, or even crash through the scrawly waves. I will journey to the southern end of the beach Ma te Aweawe (misty way), stand in that sand churning water looking out to Rakiura and know that I will never let you and this place go. But I will give my grief, a little unwitnessed flight.

(Featured image: Oreti Beach, Aotearoa New Zealand. A 26 kilometre flat stretch of smooth sand beach at the end of the South Island. Annaliese Forde)