News editors and journalists are increasingly juggling two increasingly difficult demands: the public’s right to know, and an ethical responsibility to avoid reinforcing harmful racial and ethnic stereotypes.

Journalists are expected in their code of ethics to avoid placing unnecessary emphasis on personal characteristics. However, there are times when a person’s racial or ethnic background becomes relevant, particularly in cases involving systemic discrimination or political rhetoric. Deciding when to include it however is often a matter of hot newsroom debate.

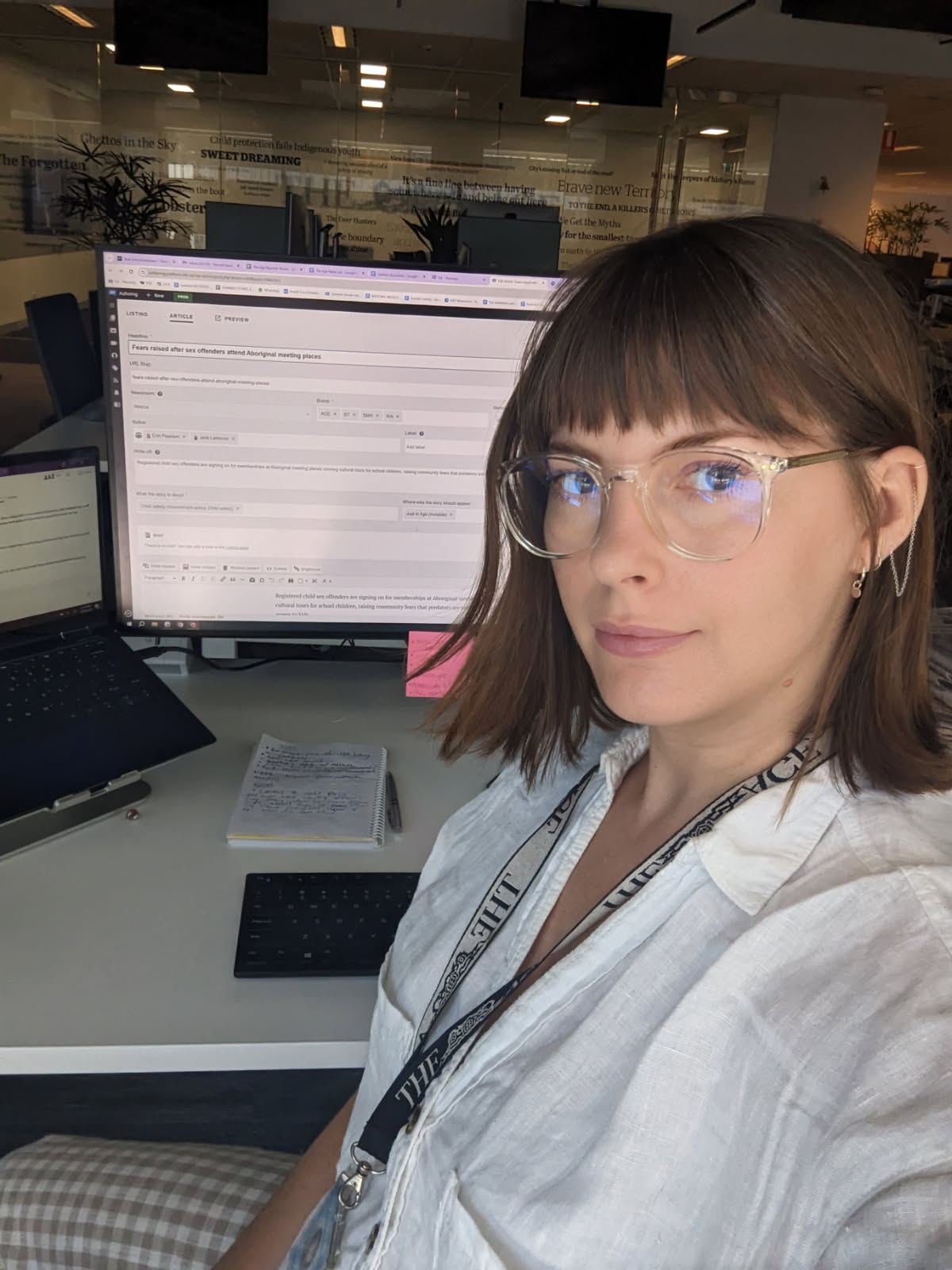

News Editor at The Age, Hannah Hawkins, says a person’s race or ethnicity is not generally included in crime reporting unless it is directly relevant.

“When Peter Dutton said a few years ago that African gangs are roaming Melbourne and terrorising people… you would have to include that [because] you’re reporting a quote,” Hawkins says.

In this case, reporting on race was unavoidable, due to the public discourse surrounding it. However, in standard crime reporting Hawkins says it wouldn’t be appropriate to identify a person’s heritage because it generally isn’t relevant.

The Race Reporting Handbook produced by Media Diversity Australia makes it clear that including a person’s racial background in crime stories, where it is not appropriate, can portray criminal activity as an ethnic trait, leading to moral panic and the stigmatisation of entire communities.

(HANNAH HAWKINS)

However, these considerations are not always clear-cut.

Hawkins recalls newsroom discussions about the use of the term “Middle Eastern crime gangs” to describe major organised crime families operating in Australia, a label she says is used by law enforcement and the crime families themselves. In this case, the decision to use the term is based not only on its official designation, but also the fact the groups self-identify with their heritage.

Hawkins says it is important to engage with the communities affected by media coverage, particularly if the person or people belong to a minority group. When in doubt, she says, journalists should ask how individuals and communities want to be identified.

A recent example in Melbourne involved a Somali refugee who was shot and killed by police in the inner west Melbourne suburb of Footscray. Hawkins says his community advocated for his racial background to be recognised, as they saw the incident as being directly relevant to his race, homelessness, and refugee status.

“There’s a lot of intersectional factors at play… and the community wanted this to be recognised,” Hawkins says.

The rise of digital publishing and the pressure to break news quickly can also complicate these editorial decisions.

Hawkins says reporters and editors at The Age are encouraged to slow down and prioritise accuracy and sensitivity.

“Rather than just beating our competitors at all costs, we’ll definitely hang onto something until we’ve got the wording right,” she says.

When a story involves a culturally or racially sensitive issue, Hawkins says the editorial team aim to have it reviewed by multiple people, including those with relevant lived experience or reporting expertise. This internal consultation process, she says, helps ensure appropriate language and framing before publication.

Hawkins says diversity within the newsroom itself is also important. Ensuring team members come from a range of backgrounds plays a key role in sense-checking stories and making sure reporting reflects different perspectives, particularly when covering minority communities.

This is central to Media Diversity Australia’s central argument that diversity within newsrooms is crucial for ethical, accurate, and inclusive journalism.

As reporters and editors adapt to the demands of digital publishing and the speed of the news cycle, they continue to weigh not just what gets reported, but how it gets reported on.

(Featured Image: William West AFP)