Soldiers stand around on the tarmac as they wait for the pre-flight routines, 11 December 2019. The soldiers were brought in from all over the country to quell the 2019 protests in Manokwari, West Papua. (Jeremy Gan)

A protest last August sparked by the anger of the Papuans, in a long exhausting conflict lasting 57 years and counting.

The sky was dark, the air was hot and humid. Manokwari, West Papua’s Rendani Airport is usually closed at night to travellers however tonight on December 11 2019 the tarmac is strewn with ground handlers, engineers and members of a special military operation unit called Brimob (Korps Brigade Mobil). The soldiers stood around the plane. A Boeing 737-900 chartered by Lion Air heading for Ambon, Maluku, as ground handlers carry their firearms on to the pressurized cabin.

Smiles were seen across every soldier’s face as they huddled around taking pictures in front of the plane. They’re going home. They carry snacks and souvenirs in plastic bags for their loved ones as they make the journey back home after months in Papua.

Later into the night at 4am, another identical plane would take another military unit to Manado, North Sulawesi. And a final identical plane in the afternoon would take the last remaining units to Makassar, South Sulawesi.

Rows of airplane stairs at the end of the tarmac, 11 December 2019. Only one flight of steps was used. (Jeremy Gan)

Ground handlers carry a box of firearms, 11 December 2019. There were roughly two trolleys full of firearms. (Jeremy Gan)

The Indonesian government brought all the officers in to quell the 2019 Papua protests.

The August 2019 protests were ignited by the anniversary of the 1962 New York Agreement between The Netherlands and Indonesia regarding the territory of West Papua. The agreement to hold a referendum for the independence of the territory, the Indonesians rigged it.

Papuan student groups protested across several cities in Indonesia which initially proceeded peacefully, but quickly devolved into violent clashes between them and the police.

An incident taking place on 16 August 2019 where 43 Papuan students in Surabaya, West Java were arrested by police after reports of a flag burning outside of their dormitory. A crowd gathered outside the residence, including far right militias from the Front Pembela Islam (the Islamic Defenders Front), and Pemuda Pancasila (the Pancasila Youth). “Monkeys!” the crowd shouted at the students hunkered in their dormitory as the crowd film the event on their phones.

On 19 August 2019, protests all around Papua would start. A protest of several thousand began in Manokwari, West Papua which devolved into a riot. Some rioters looted and set fire to stores, vehicles were lit up, and the streets were filled with ashes from the burning.

The protesters threw rocks at the police which injured three officers. This scene would be replicated in many Papuan cities. The riots would end with the government buildings set ablaze in Wamena, Sorong, Jayapura, and Manokwari, West Papua.

The burnt down parliament in Manokwari during the protests, 4 December. Cities Wamena and Sorong also had government buildings burnt. (Jeremy Gan)

“I ran, I just ran as fast I could,” a business owner in Manokwari told me – his bakery was stormed while him and his staff was still inside. “My heart was pounding harder than it ever had.”

The protests would go on to last until September onwards. The Indonesian government utilized different methods of curbing protests, bringing in units of Brimob from across the country to assist in the protests, and intimidating and harassing journalists, protesters, and human rights activists.

According to The International Coalition of Papua that compiled and listed all fatalities, the protests resulted in 59 deaths. 40 of the deaths originated from Wamena, West Papua. Controversially the government would enact internet shutdowns all over Papua. Declaring “a state of emergency” to enact it, in an effort to curb more protests it effected businesses and communication all-round the region. The shutdown would be ruled as a violation of the law by the Jakarta State Administrative Court on 3 June 2020.

“A friend moved his entire office to the hotel in town because it was the only place with working internet,” said the airport manager who allowed me to photograph the soldiers. “It was absolute chaos.” He proceeded to show me videos and photos of protesters smashing the windows of Domine Eduard Osok airport in Sorong, West Papua. “They absolutely trashed the place” he said. The tone of his voice lowered, “This whole thing has been going on for way to long, when are they going to make peace?”

Roman (name has been changed for anonymity), an activist who took part in the protest at Jayapura said, “Some people see the protests as a reason to burn, loot and harm people.” He told me sarcastically, “it’s Indonesia, what do you expect?” He was lean, a calm look in his eyes, a constant soft smile on his face as we talked on a WhatsApp call. “There’s the thinking in Indonesia where every political gathering, be it a Governors speech, a rally, or demonstration, that most there were paid protesters.”

In a frustrated tone, he said “I hope no one in the protests was paid.” He rubbed his forehead as he said, “We’re already fight an uphill battle against the [Indonesian] government, and having this mentality only harms our cause.” Despite the local parliament building’s demise in the protests in Manokwari, most of the government buildings in the city never saw the protest. The governors, regent, and provincial offices are situated atop a hill, roughly 40 minutes’ drive from the city where the protests were held.

An empty security post in the governor’s hill, 9 December 2019. One of dozens of empty posts. (Jeremy Gan)

“We never would’ve made it up there,” said Herman (name has been changed for anonymity), a political activist who was in the Manokwari protests. “It would’ve been a bigger bloodbath than it already was.”

The governors hill is lonely. Not a worker seen walking around during work hours. Rather the property is dotted with empty security posts, billboards which constantly flash propaganda, and buildings so grand it stands out from the surrounding scenery of green. As we drive down the hill, I spot an array of solar panels hidden in the bush. “They’re not connected to anything, it’s all for show” said my driver. Bewildered, I asked why they would do it. He just shrugged his shoulders.

“It’s insane how they spent all the money from the [Indonesian] government to build a shrine to themselves,” said Herman in an exhausted tone. “My father fought the Indonesians for our land, and now I’m doing the same thing” said Herman. His eyes were alert, constantly looking behind the phone as we talked on a WhatsApp call. I asked him what happened to his father, he said, “He was killed.” He didn’t elaborate further.

“I call it the 20-year cycle” said John Martinkus, a journalist who has been covering Indonesian civil conflicts since the mid-90s. “Activists will have kids, they’ll get killed in some way, then their kids will grow up to their 20s, have kids, and fight the same cause.” He said Indonesian government cycles itself. Describing as a pattern by the way they respond to a threat coming from a territory if theirs. “It happened in East Timor, and it’s happening again in West Papua.”

The conflict won’t anytime sooner. Its perpetrators won’t be tried, and the Indonesian government won’t face any repercussions. “I’m enough of a realist to know it’s never going to happen,” he said. But independence is still possible for Papuans. “If the international community comes together to apply pressure for a second referendum” said Martinkus. “It worked for East Timor, and might work for West Papua as well.”

The independence of West Papua means the loss of billions of dollars of natural resources in the land, money from the international companies harvesting it, and would give more incentive for rebelling provinces to push for independence. But it will be best in the long run for everybody”, Martinkus told me. The fight for independence in the region will still spill blood.

As I talked to Martinkus, he compared the protests in Papua to the Black Lives Matters movement happening all around the globe. It was a sign that they had enough. A systematically oppressed and exploited group which has been put down for decades has now rebelled against those who put there. Leader after leader killed, generation after generation fighting, decade after decade goes by. But the fight for independence and justice goes on. The biggest of its kind, it sent a message to the Indonesians that they demand their independence.

When I talked to both Roman and Herman, they expressed a sense of fear and exhaustion for the future. As Herman said “It’s a disappointing cycle that never ends.” But there was a surprising amount of optimism. “I want to fight until we get justice” he told me. “We won’t get it in one day, it’s an effort that builds up after years of fighting, and we’ll be there to fight for it,” he said smiling at me.

It took me back that someone in his position could have such a positive outlook. In a country and world that barely recognizes your struggle. Citizens outright denying any form of Papua independence, let alone aware of it. Media and individuals denied, censored, arrested, and detained for discussing about it.

It’s hard to look at the state the Papuans have been treated to and believe there has been no global backlash towards the Indonesian government. The lifelong racism, the stigmatisation, the exploitation. The Black Lives Matters movements has allowed the worlds oppressed to fight back against their oppressors, yet the Papuans will likely not find justice and independence in the near future unless the rest of the world takes notice.

“Who wouldn’t?” responded Roman when I asked if he was scared for his life in the protests against the government. I then asked a question about dealing with racism, and he directed the answer at me, an ethnic Chinese Indonesian. “I bet you’ve had to deal with racist Indonesians before. The history of ethnic cleansing by the [Indonesian] government is baked into their history, yet it’s never taught in schools. It happened with your people; it’s happening with us. Anybody different will be shot dead.”

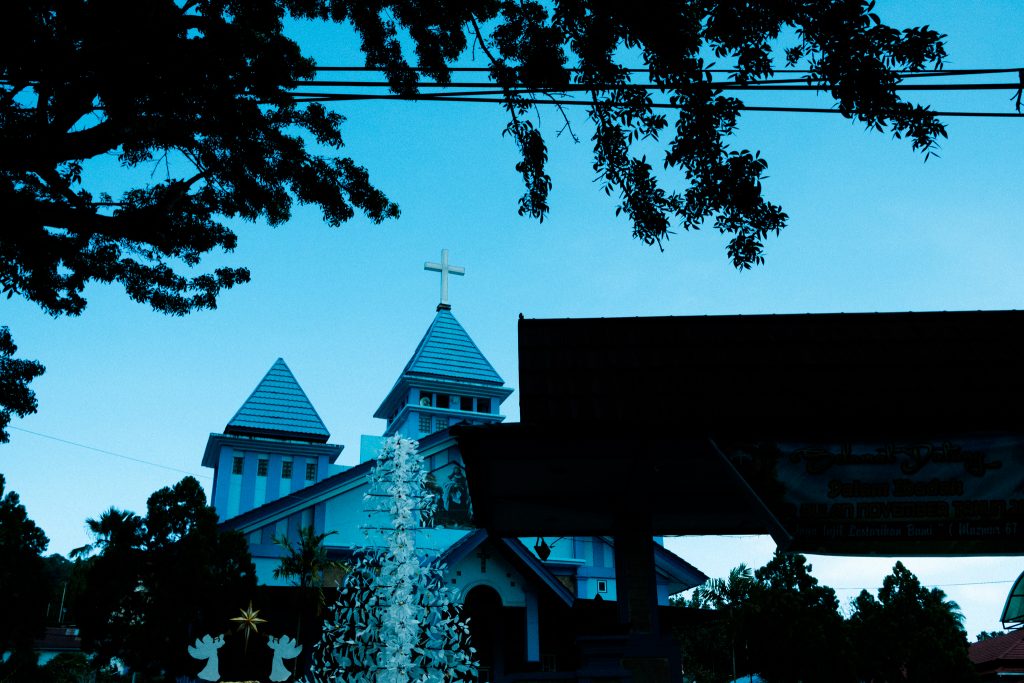

A church in Manokwari, 1 December 2019. Papuans are predominantly Christians, a minority in the world’s largest Muslim country. (Jeremy Gan)