First Nations people have lived on Australian land for upwards of 60,000 years, yet, for the last 200 or so, many have had to speak the language of their invaders.

Since colonisation, Aboriginal English has evolved from a pidgin language, necessary to communicate with colonisers, to a means of expressing identity and communicating every day.

An estimated 80 per cent of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations speaks Aboriginal English, according to the University of Western Australia’s senior linguistics lecturer Dr Celeste Rodriguez Louro.

Despite its prominence in particular communities though, Dr Rodriguez Louro says Aboriginal English’s coexistence in a society built on “Standarised Australian English” (a.k.a. Standard Australian English or SAE) “creates a lot of tension”:

Dr Rodriguez Louro – who, in her research, always collaborates with Noongar academic Glenys Collard – says most of the world’s major languages live by a “standard language ideology”.

“[It’s] this idea that standard language will get you places,” she says.

“If you don’t command standarised language, you’ll be left out.”

Features of Aboriginal English

Like any language, Aboriginal English has its own structure, guidelines and lingo:

- Forms of the verb “be” are regularly dropped (e.g. “She my sister”).

- “Them” is used in place of “these” or “those”

- Question structure is likely to be uninverted (e.g. “Richmond’s your footy team?” rather than “Is Richmond your footy team?”).

- The “h” sound is commonly left out of the beginning of words.

- Respected figures – or senior people a speaker has never met – are referred to as Auntie or Uncle.

- The possessive “-s” suffix is often omitted (e.g. “I drove my dad car” rather than “I drove my dad’s car”).

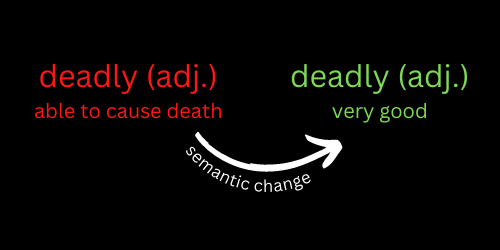

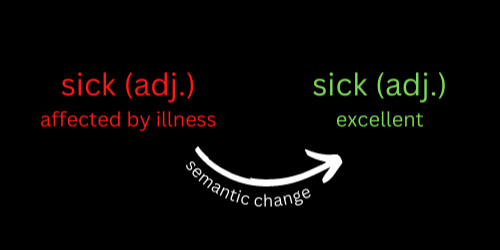

- “Hungry” and “deadly” can mean “great”.

And similarly…

The oft-held view that this different structure represents poor or broken English is an ignorant one. If speakers can communicate through a particular language, then why should that language be considered inferior?

Has Indigenous language influenced SAE?

To gauge Aboriginal English’s influence on SAE is a difficult task for researchers – Aboriginal English has been umbilically linked to SAE since its birth, as much of the language draws on the English spoken by the British and Irish.

However, one key field in the linguistics of Australian culture continues to lean heavily on ancestral Indigenous languages.

Much of Australia’s flora and fauna have English names borrowed from millennia-old native languages, be it a barramundi (from central Queensland’s Gangulu language), a galah (north-west NSW’s Gamilaraay) or a coolabah tree (from north-west NSW’s Yuwaalayaay).

Why flora and fauna specifically? Dr Rodriguez Louro has the answer:

Billabong (from central NSW’s Wiradjuri), boomerang (precise origin unknown), coo-ee (“come here” in south-west Sydney’s Dharug) and yakka (“work” in Brisbane’s Yagara) are a few exceptions to the flora and fauna borrowing rule, yet still largely lie within the outdoors domain.

According to Dr Rodriguez Louro, when used by non-First Nations people, use of Aboriginal English-specific or borrowed words can swing between totally acceptable and politically incorrect.

“It depends on when the word entered [English] and what it refers to,” she says.

Whilst opinions differ in all cultural groups, Dr Rodriguez Louro’s general advice for non-Aboriginal English speakers is this: if there’s another word for it, use that other word.

Take kookaburra (from Wiradjuri), for example. There’s only one word for a kookaburra, so use that.

If a speaker chooses to say “mob” or “deadly” though, they’re likely making a conscious and potentially offensive choice to opt for that over “people” or “great”.