By Madeline Jackel, Serena Seyfort and Danni Roberts

When Ashraf Manassa sought asylum in Melbourne after fleeing Egypt, he never thought he’d feel unsafe in his own Melbourne home.

Ashraf and his wife’s Bundoora apartment was raided in June this year.

The couple returned home one evening to find their home ransacked, with over 30 thousand dollars worth of possessions missing.

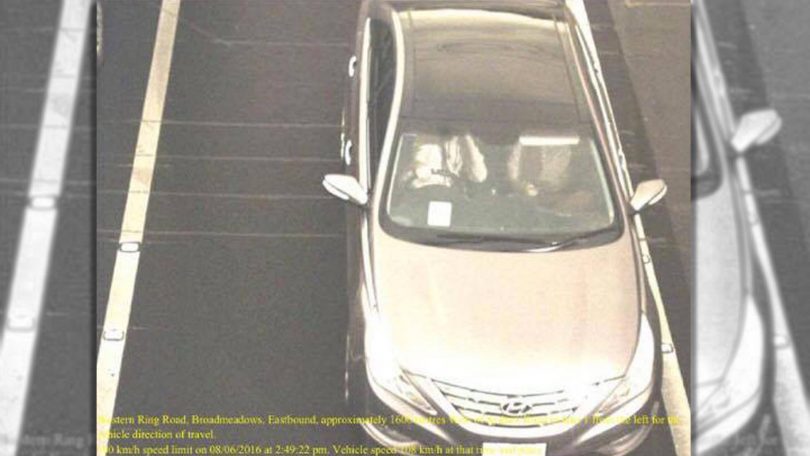

The thieves stole valuable possessions, including birth certificates and passports, before returning days later to drive off with their car.

“I didn’t believe this could happen in Australia. This had never happened to me in Egypt, even with the corruption in the country and the crime,” said Mr Manassa.

“For a few days I thought, yeah, it’s not safe in this country. I’ve got to leave.”

Victoria’s crime rate has soared by an alarming 12.4 per cent in the past year, according to the Crime Statistics Agency.

Car thefts have increased by 22 per cent across the state, while house burglaries are up almost 14 per cent.

With more than half a million offences recorded, police allege Melbourne’s escalating youth gangs have a part to play.

A recent spate of arrests found that Melbourne’s Apex Gang are recruiting those as young as twelve.

Professor of Criminology, Rob White, says young people facing social exclusion are more susceptible to joining these gangs.

“I don’t think the key issue is gangs at all. Really the issues are standard criminological issues of marginalisation,” he said.

“In the end, the core issue has to deal with the social conditions within which these young people are growing up.”

The Helping Hand Project is working with some of those most at risk of social exclusion: young migrants.

Volunteers provide supportive mentoring for 13-21 year olds to assist them with settling into Australian culture.

Program psychologist Conrad Aikin believes community support is the key to helping these young people adjust to their new lives.

“They have all these sorts of challenges on top of what they’ve dealt with in the past and not knowing their way around and often not having the sort of supports and connections that people need to get on with things in their lives,” said Dr Aikin.

Projects like Helping Hand are a step forward towards creating an inclusive environment for Melbourne’s young people.

“That’s a good thing, that’s a good thing for everyone, and that’s a good thing for younger refugees.”