In January 1995, The Age become one of the first newspapers worldwide, and the first in Australia, to launch its own website.

If you look through early editions still available on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, you might find fantastically-retro Web 1.0-era design, or interviews with not-so-retro media figures like Rupert Murdoch. But you’d also find stories that would not be out of place in the paper’s modern online edition, organised then as they roughly are now, under headings like ‘News’, ’Sport’, ‘Business’, and prophetically, ‘Computers’.

This echoes what Wendy Tuohy, who was a journalist at The Age in 1995, and is now a senior writer there covering social issues, says about the impact of the digital and multimedia revolution on the print newspaper industry. While technologically has leapt forward during her career in a way she describes as from ‘horse-and-cart to SpaceX’, certain fundamentals have stayed the same: ‘News values don’t change.’

While advances in data journalism have allowed publications to target readers with greater precision, the kinds of stories they are interested in remain consistent, says Tuohy.

This has a basis in independent research: a 2016 study identified ‘shareability’ as a news value linked to the rise of digital and social media, but found in an analysis of UK newspapers that ‘bad news’, one of 12 values identified in a seminal 1965 study, was still the most common news value, and the third most common news value on stories shared on social media itself.

However, Tuohy is keen to stress that, while basic journalistic skills have stayed the same, the techniques used in by the industry are in a state of ‘constant flux’. This is reflected in graduate cadetships increasingly advertising for ‘cross-platform’ or ‘multimedia’ journalists, and the expectation that journalists record their own podcasts and video and take their own photos, which has lead, among other things, to newspapers employing fewer photojournalists.

Traditional media outlets have also been quick to embrace new social media. The Guardian in Australia was early to adopt a TikTok specialist, Matilda Boseley, and print outlets like The Age and The Herald Sun have since followed suit.

Journalists are rarely given the new training in the new technologies the industry hungrily assimilates and often ‘learn on the job’, or are self-taught, Tuohy explains. As Boseley recently told an audience at the University of Melbourne: ‘If you want something done, be able to have the skills to get all the steps done yourself.’

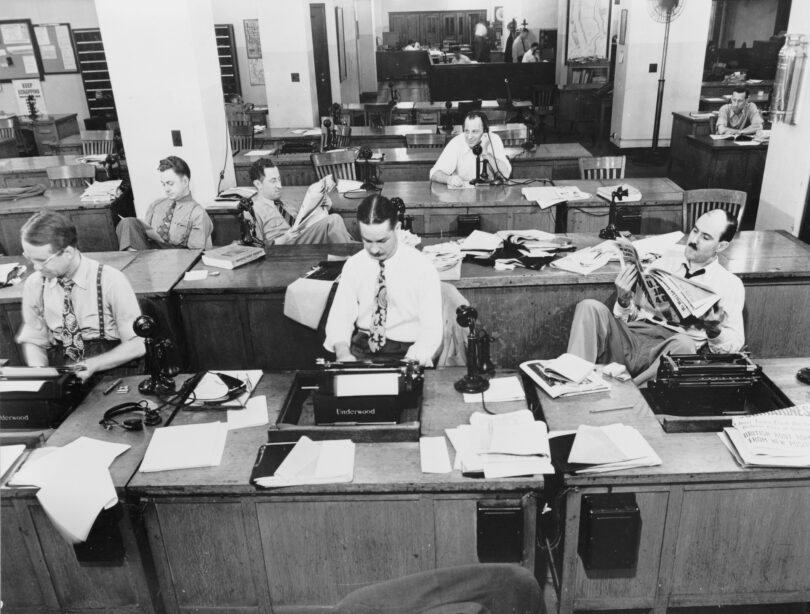

Samuel Johnson characterised journalists in 1758 as possessing ‘neither genius or knowledge’. This harsh assessment, as Richard Orange and Barry Turner have written, hits upon a journalistic truth: journalists have always been expected to move around within media organisations, to put aside swiftly-gained expert knowledge and start again in different roles, cover a different beat or specialist round. The new requirement that journalists work across media platforms is just another development in this long-understood flexibility.

Tuohy praises the impact the visual, confessional emphasis social media has had on the way audiences engage more directly with those experiencing social issues, as they now expect to hear directly from the subjects of stories, not simply from government agencies.

In this sense, multimedia journalism clearly has the potential to enhance and not just replace the output of the traditional newsroom: although it continues to shrink, it may yet survive.