Part I: The Dynasty

By Evan Morgan Grahame

Hashim Khan was the first Pakistani to win the British Open, the oldest and most prestigious international squash tournament. Having travelled to London to contest the tournament at the Lansdowne Club, Khan’s breezy 9-5, 9-0, 9-0 victory over Egyptian Mahmoud Karim – winner of the four previous Opens – saw his nation curl their fingers around international squash for the first time.

It was 1951, and marked the beginning of a vice grip Pakistan would maintain on the sport for most of the next half-century. Hashim Khan would go on to win seven Opens.

From 1951 until 1998, there would be only seven British Open men’s finals played that didn’t include a Pakistani athlete. To put it in a larger context, a Pakistani squash player has won 42% of the total available men’s British Open titles since 1929 – there was a seven-year break for World War II – and has appeared in 58% of the finals.

The other main international squash tournament is the World Open – now called the World Championships – which began in 1976 and is staged in a different country every year, including being held in Pakistan three times.

The Pakistani dominance of that competition is just as supreme; for 20 straight years, from 1976 until 1996, a Pakistani was either the men’s winner or runner-up.

There have been periods of one-nation dominance in other sports – in tennis, for instance, between 1956 and 1971, there was only one Wimbledon final that didn’t involve an Australian. But as far as genuinely international sports go, that have been contested over multiple decades, nothing comes close to the degree of control Pakistan enjoyed over world squash.

Hashim Khan blazed the trail, leading the way for the two generations of legendary Pakistani squash players that would follow.

The bold lines of a modern squash court (Photo: via PublicDomainPictures.net)

Jahangir and Jansher

The 1980s and 90s saw two brilliant jewels cut, both of which would eventually bet set in the crown of Pakistani squash. But first, before our star players enter, let’s establish the scene.

In 1957, the British Open semi-finals brackets were populated entirely by Khans, all related; Hashim and his younger brother Azam faced off on one side of the draw, then a third Khan brother, Roshan, took on his nephew Mo Khan on the other side. Mo was just 19 at the time.

The Khan family, ubiquitous in squash in the 50s and 60s, would continue producing players to dominate the next two decades.

Roshan had two sons, Torsam and Jahangir. Torsam, the elder son, developed into a lithe, elegant player, who was rising up the world rankings in the late 70s. He was 27 when he suffered a sudden heart attack in 1979, playing in Australia, and died. It was a devastating blow to his younger brother Jahangir, who was 15.

Torsam had been the shining light of his generation of players, and many feared that with his death the flame of Pakistani squash might fade quietly to embers. Hashim Khan’s generation had all grown old and retired, and Australia had taken over as the dominant squash-playing nation.

From 1974 until 1981, Melbourne’s Geoff Hunt won seven of eight British Opens, including six consecutively. Hunt also won the first four iterations of the World Championships, beating Pakistani opponents in all four finals.

The Pakistani grip was slipping; Qamar Zaman, another great Pakistani player, lost to Hunt in the British Open finals three years in a row. A saviour was needed.

It was at this point, in the early 80s, that Jahangir Khan, once a sickly child but now a young prodigy, strode into the light. Determination steeled by his brother’s tragic death, and a player who enjoyed a seemingly bottomless reservoir of stamina on the court, Jahangir beat Hunt in the 1981 World Championships, aged just 17.

This victory marked the start of a winning streak that would stretch on into sporting folklore; for five years – 555 estimated matches – Jahangir went unbeaten. Four straight World Championships and 10 straight British Open titles later, and Jahangir Khan was widely considered the greatest men’s squash player to ever live.

Australian squash great Chris Dittmar, one of the few consistent challengers during this period, remembers the era with a sort of wry humour.

“Unfortunately for me, I was number 2 in the world for approximately 10 years because of the dominance of Jahangir Khan,” Dittmar said. “He is arguably the best player we’ve ever seen and came along as a young player and immediately lifted the standard of how we played, and how we had to train and prepare. Jahangir had sublime skill and played the game at a pace we hadn’t seen before. He was fit, strong, skilful and always fair.”

The numbers behind squash’s greatest men’s player. (Graphic: by Evan Morgan Grahame)

Khan knew exactly how good he was, and wasn’t afraid of showing it.

“I am playing more on the hardball circuit [a separate, US-based version of the sport] because sometimes I lose at that game and I often find myself under pressure,” Khan said in 1985. “Winning all the time so easily in the international game bores me.”

As Jahangir’s prime ended, Jansher Khan took over – yes, another Khan, but this time unrelated to all the aforementioned Khans. Jansher was another Pakistani, six years Jahangir’s junior.

Jahangir’s reign lasted until the early 1990s, when he won his last British Open; at that point Jansher assumed the mantle, winning the next six Opens, as well as eight out of 10 World Championships between 1987 and 1996.

Jansher’s best asset on the court was his movement; in a sport played at such a frenetic pace in such tight quarters, the more agile, graceful and precise your movement can be, the better a player you become. Squash is a sport where disguised drop-shots, or sudden changes in angle can prove decisive mid-rally.

Every shot your opponent plays is designed to test the extent of your athletic capabilities, to stretch every sinew and tighten every fibre. As far as the ability to cope with all of this, Jansher Khan was unrivalled. Again, Dittmar – who lost four World Championships finals to Jansher – remembers his great foe:

“Jansher was totally different,” Dittmar recalls. “He didn’t possess the racquet skill of Jahangir but he was an incredible athlete. We had never seen such retrieving ability or such fitness in a squash player. Everyone at that level was fit but after two brutal hours on court, when anyone else would start to flounder, he was still sprinting around at full speed. It was superhuman!”

When Jansher’s prime ended in the late 90s, and he faded from relevance, so too did Pakistani squash.

There was no successor this time, and the last two decades have been barren. There have been no Pakistani men in the finals of either of the two major tournaments since Jansher Khan lost the 1998 final; the nation’s iron grip weakened, slipped, and finally let go for good.

Part II: Reviving the Game

By Julian Di Nezza

After more than four decades of dominance in the sport, Pakistan has experienced fluctuating results in recent years that have left the former powerhouse wallowing in mediocrity.

In 2009, the attack on a Sri Lankan cricket team bus forced the hand of the ICC to ban all international matches in Pakistan. This created a ripple effect that saw other sports and athletes follow the ICC’s lead by refusing to visit the country.

Finally, after eight years in the sporting wilderness, Pakistan is once again hosting players from across the globe to compete in tournaments like the Pakistan Rangers Sindh Squash Championship in Islamabad.

Pakistan Squash royalty Jahangir Khan stated that “the participation of well-known international players in events in Pakistan was a great step forward for the sport in the country.”

“The revival of squash after nearly a decade will help the development of the game in the country for youngsters who want to take up the sport as a profession,” said Khan.

Undoubtedly there are areas for Pakistan to be concerned over.

Pakistan’s participation rates across all sports have dropped because of a lack of funding. According to many, this is the main reason why squash has also begun a slow decline into insignificance.

“Pakistan’s sports budget is the lowest in South Asia, less than that of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and even Afghanistan,” said Khalid Mahmood, secretary of Pakistan’s Olympic Association.

The tool of the squash player’s trade (Photo: via VisualHunt.com)

In attempt to rejuvenate the once idolised sport, the once-pedigreed nation is now pinning its hopes on new faces to return Pakistan to its glory days. Muhammad Ammad has been labelled the next Jahangir Khan and, at the tender age of 15, he is already sending shock waves throughout squash the world.

His explosive and aggressive play saw him become the first Pakistani to reach the quarter-finals of the British Junior Squash Championship after almost 10 years.

Fast forward a few months, and the teenager – who represents the Pakistan Air Force – showcased his array of shot-making skills at the Qatar Junior Squash Championships in Doha, dismantling his highly-fancied Indian opponent in a little over 17 minutes.

Ammad was not the only Pakistani to win in Doha; Pakistan made it a clean sweep in all three categories – an dominant performance that once again puts them back on the map.

Still, as encouraging as the Doha triumph is, the issue of Pakistan’s depleted budget has closed many doors on the sport, but has managed to open new avenues that the country once thought were unimaginable.

Australia – once a bitter rival but today a close ally, has united with the Pakistan Squash Federation in launching a development project called the ‘The Squash Classroom’.

The initiative which was launched in 2017, uses squash to promote health, gender equality and education for youth in Pakistan.

Australia’s acting High Commissioner in Pakistan, Jurek Juszcyk, said that “more than 600 Pakistanis will participate in the project” with the program expanding Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi and – of course – Peshawar.

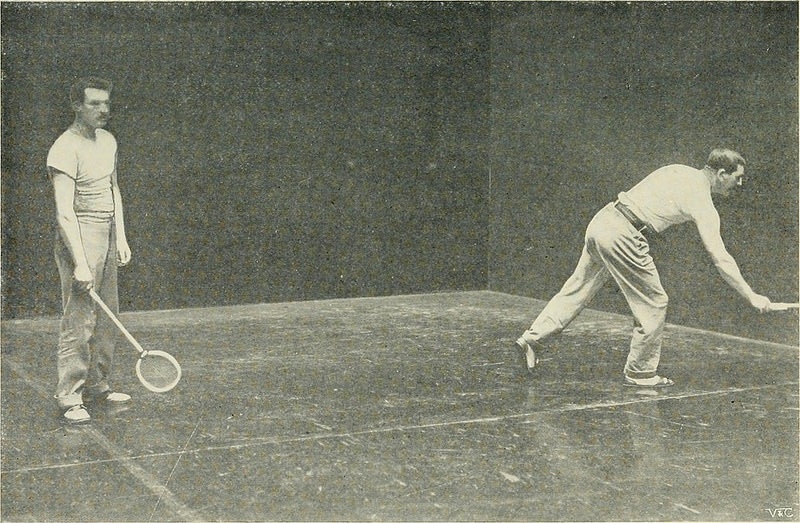

Two players in action at the 2013 Commonwealth Games (Photo: via VisualHunt.com)

Crucially, one of the biggest problems Pakistan squash faces is the outdated coaching methods that have seen them slump into ‘the dark-ages’ of nurturing and developing talent.

The deputy director of the Pakistan Sports Board, Waqar Ahmed, said federations have had their hands tied as they cannot afford to hire good coaches familiar with the latest coaching skills.

“Without the infrastructure we can do a lot,” said Ahmed. “But without the techniques you cannot win.”

Coinciding with the government funded program, twenty youth leaders and mentors completed a Level 1 Coaching Course certified by the Asian Squash Federation in an attempt to kick-start a new generation of modern coaching. However, Pakistani squash is not out of the woods by any means of the imagination.

A poor showing in this year’s Asian Games, and the Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast, has seen some Pakistani media organisations describing the future as “quite bleak”.

National coach Fahim Gul was fired for the poor showings, while Pakistan’s best senior squash player was barred from training at Mushaf Squash Courts PNSA directors.

By and large, for Pakistani squash it’s a matter of ‘one step forward and two steps back’. Still, if you look closely, the foundations have been laid for the country to return to its glory days and begin a period of prosperity both on and off the court.

[…] was a dominant force in World Squash since its independence. Hashim Khan was the first-ever hero for Pakistan in the […]