The recent push for transparency in the fashion industry has affected a small proportion of companies to implement positive changes to their supply chains.

But this change is far from enough.

According to Choice in 2014, Australian consumers on average were spending $2,288 on clothing and footwear per year.

A wardrobe over flowing with clothes, some never even worn. This sort of clothing collection has become a statistical norm for the the everyday Australian. Ruby Staley

However, according to Oxfam, in 2017, only 4 per cent of what is spent goes to the wages of the workers who produce the apparel.

That’s just $91.52 in the garment worker’s pocket for creating an entire year’s worth of clothing, roughly 27kg, for an Australian.

And as the the second-largest consumer of new textiles in the world, do Australian customers even care where their money ends up?

To combat these staggering numbers and spread some much-needed awareness, some Australians are stepping up to the plate and illuminating the realities of large scale apparel production.

Not-for-profit organisation, Baptist World Aid Australia, released their annual ethical fashion guide which rates popular fashion producers from an A+ to an F.

With the sixth edition of the report this year looking at 130 companies, representing about 460 brands, the organisation bases the grading on a range of criteria including worker wages and conditions, child labour and environmental degradation.

With “38 per cent of the companies actually improving their grading from last year”, says Baptist World Aid Australia CEO, John Hickey, it seems that positive change is being made.

While some brands such as Patagonia, adidas and Bonds scored highly with A to A+, 95 per cent of companies fail to pay a living wage to all workers.

Meanwhile, only small proportion (8 per cent) of these brands demonstrated the presence of trade unions or collective bargaining agreements in their factories.

“A lot of companies in the industry just turn a blind eye to what they can’t immediately see, using excuses like “we don’t control those companies””, says Hickey.

Additionally, he says that the small amount of companies “that can demonstrate they are paying a living wage really only relates to the last stages of production”.

This means brands who seemingly scored well, don’t protect their workers nor offer them a minimum wage even though “48 per cent of these companies have a stated intention and policy to move to living wage”.

Ethical Clothing Australia is another not-for-profit organisation, funded by the Victorian government that works with local textile and apparel companies through a voluntary accreditation program.

The ECA accredits companies based on their management of their supply chains, ensuring they are completely transparent and legally compliant.

National manager, Angela Bell, says Australian workers of accredited companies receive “their legal entitlements and work in safe conditions”.

Bell explains that ECA have over 100 businesses as part of the program, saying it “is a positive indication that the industry is recognising the need for more transparent and ethical framework.”

Ethical clothing company, Re-Make, works to encourage consumers to embrace the slow fashion movement which involves making sustainably responsible decisions when purchasing clothing.

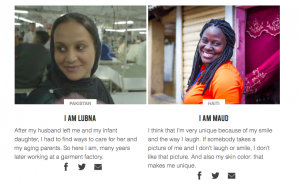

With a focus on connecting consumers with producers, Re-Make developed the “meet the maker series” which is an interactive feature of their website that allows customers to learn about and connect with the workers.

A snapshot of Re-Make’s Meet the Maker Series where customers can get to know the people who make their clothing. This feature was created in an attempt to humanise factory workers and connect consumers with the impacts of their spending. Ruby Staley

Founder, Ayesha Barenblat, explains that this feature encourages customers to appreciate the “hard work of this forgotten #girlboss at the other end of the supply chain”.

Barenblat encourages Re-Make’s shoppers to “recognise that we can wear our feminist values with our shopping choices”.

However, as consumers, buying from ethical and sustainable brands is not the only way to push for positive change.

John Hickey says, “the best way to get change is to get the people that those companies rely on to actually be speaking out loud about this too – consumer power will keep driving this positive change”.

To aid this process, Baptist World Aid Australia have put together an ethical “shopping guide” on its “’End Poverty’ app” that enables contact between buyer and producer.

The mobile app’s unique feature of linking consumers with companies can allow for invaluable direct feedback to occur.

Reading through the ‘Ethical Fashion Guide’ on Baptist World Aid Australia’s mobile app. The app also encourages communication between buyers and brands to promote ethical supply chains. Ruby Staley

“I think there is a general trend of consumers and companies realising that just being cheap isn’t good enough and you have to think more about a more sustainable model of business and also sustainable about how you treat your supply chain”, says Hickey. “It’s this sort of people power around engaging with this and communicating with companies that promotes ethical supply chains”.